優質程式文章備份

備份優質的文章,你可以把這裡作為一個書籤頁,原文請到原始網站查看。

- 閒聊 - 「好程式」跟你想的不一樣! 初讀「重構」有感

- 重構筆記 - 壞味道 (Bad Smell)

- 重構筆記 - .NET 壞味道補充包

- 重构-改善既有代码的设计

- 能抓耗子的就是好貓?閒談程式碼 Anti-Pattern

- 程式碼中的抽象

- 淺談「錯誤的抽象」

- 淺談「重覆程式碼」

- 《先整理一下?個人層面的軟體設計考量》讀後心得分享

- Write code that’s easy to delete, and easy to debug too.

- Goodbye, Clean Code

- The Wrong Abstraction

- Repeat yourself, do more than one thing, and rewrite everything

- The Law of Demeter Creates More Problems Than It Solves

- 【Code Review】十行循环变两行?argparse注意事项?不易察觉的异常处理?

- 【Code Review】传参的时候有这么多细节要考虑?冗余循环变量你也写过么?

- 如何優雅地避免程式碼巢狀 | 程式碼嵌套 | 狀態模式 | 表驅動法 |

If there are any copyright issues, please contact us.

錯誤的抽象

The Wrong Abstraction, Sandi Metz

The Wrong Abstraction

I originally wrote the following for my Chainline Newsletter, but I continue to get tweets about this idea, so I'm re-publishing the article here on my blog. This version has been lightly edited.

I've been thinking about the consequences of the "wrong abstraction." My RailsConf 2014 "all the little things" talk included a section where I asserted:

duplication is far cheaper than the wrong abstraction

And in the summary, I went on to advise:

prefer duplication over the wrong abstraction

This small section of a much bigger talk invoked a surprisingly strong reaction. A few folks suggested that I had lost my mind, but many more expressed sentiments along the lines of:

The strength of the reaction made me realize just how widespread and intractable the "wrong abstraction" problem is. I started asking questions and came to see the following pattern:

- Programmer A sees duplication.

- Programmer A extracts duplication and gives it a name.

This creates a new abstraction. It could be a new method, or perhaps even a new class. 3. Programmer A replaces the duplication with the new abstraction.

Ah, the code is perfect. Programmer A trots happily away. 4. Time passes. 5. A new requirement appears for which the current abstraction is almost perfect. 6. Programmer B gets tasked to implement this requirement.

Programmer B feels honor-bound to retain the existing abstraction, but since isn't exactly the same for every case, they alter the code to take a parameter, and then add logic to conditionally do the right thing based on the value of that parameter.

What was once a universal abstraction now behaves differently for different cases.

7. Another new requirement arrives.

Programmer X.

Another additional parameter.

Another new conditional.

Loop until code becomes incomprehensible.

8. You appear in the story about here, and your life takes a dramatic turn for the worse.

Existing code exerts a powerful influence. Its very presence argues that it is both correct and necessary. We know that code represents effort expended, and we are very motivated to preserve the value of this effort. And, unfortunately, the sad truth is that the more complicated and incomprehensible the code, i.e. the deeper the investment in creating it, the more we feel pressure to retain it (the "sunk cost fallacy"). It's as if our unconscious tell us "Goodness, that's so confusing, it must have taken ages to get right. Surely it's really, really important. It would be a sin to let all that effort go to waste."

When you appear in this story in step 8 above, this pressure may compel you to proceed forward, that is, to implement the new requirement by changing the existing code. Attempting to do so, however, is brutal. The code no longer represents a single, common abstraction, but has instead become a condition-laden procedure which interleaves a number of vaguely associated ideas. It is hard to understand and easy to break.

If you find yourself in this situation, resist being driven by sunk costs. When dealing with the wrong abstraction, the fastest way forward is back. Do the following:

- Re-introduce duplication by inlining the abstracted code back into every caller.

- Within each caller, use the parameters being passed to determine the subset of the inlined code that this specific caller executes.

- Delete the bits that aren't needed for this particular caller.

This removes both the abstraction and the conditionals, and reduces each caller to only the code it needs. When you rewind decisions in this way, it's common to find that although each caller ostensibly invoked a shared abstraction, the code they were running was fairly unique. Once you completely remove the old abstraction you can start anew, re-isolating duplication and re-extracting abstractions.

I've seen problems where folks were trying valiantly to move forward with the wrong abstraction, but having very little success. Adding new features was incredibly hard, and each success further complicated the code, which made adding the next feature even harder. When they altered their point of view from "I must preserve our investment in this code" to "This code made sense for a while, but perhaps we've learned all we can from it," and gave themselves permission to re-think their abstractions in light of current requirements, everything got easier. Once they inlined the code, the path forward became obvious, and adding new features become faster and easier.

The moral of this story? Don't get trapped by the sunk cost fallacy. If you find yourself passing parameters and adding conditional paths through shared code, the abstraction is incorrect. It may have been right to begin with, but that day has passed. Once an abstraction is proved wrong the best strategy is to re-introduce duplication and let it show you what's right. Although it occasionally makes sense to accumulate a few conditionals to gain insight into what's going on, you'll suffer less pain if you abandon the wrong abstraction sooner rather than later.

When the abstraction is wrong, the fastest way forward is back. This is not retreat, it's advance in a better direction. Do it. You'll improve your own life, and the lives of all who follow.

News: 99 Bottles of OOP in JS, PHP, and Ruby!

The 2nd Edition of 99 Bottles of OOP has been released!

The 2nd Edition contains 3 new chapters and is about 50% longer than the 1st. Also, because 99 Bottles of OOP is about object-oriented design in general rather than any specific language, this time around we created separate books that are technically identical, but use different programming languages for the examples.

99 Bottles of OOP is currently available in Ruby, JavaScript, and PHP versions, and beer and milk beverages. It's delivered in epub, kepub, mobi and pdf formats. This results in six different books and (3x2x4) 24 possible downloads; all unique, yet still the same. One purchase gives you rights to download any or all.

Posted on January 20, 2016 .

淺談「錯誤的抽象」

淺談「錯誤的抽象」

我達達的馬蹄是美麗的錯誤

我不是歸人,是那匹馬

在「2014」年的「RailsConf」中,一位美國工程師「Sandi Metz」提出了「錯誤的抽象」的這個概念;「錯誤的抽象」,其原文為「The Wrong Abstraction」,「Sandi Metz」說,她認為「重覆程式碼(Duplicated Code)」所造成的「技術債」比起「錯誤的抽象」所造成的「技術債」還要「低廉」,因此,她寧願接受「重覆程式碼」的存在,也不要冒著可能導致「錯誤的抽象」的風險,完整內容請參考「RailsConf 2014 — All the Little Things by Sandi Metz」。

在「Sandi Metz」的敘述中,我們可以得知,「Sandi Metz」認為,「錯誤的抽象」會造成相對昂貴的「技術債」,並且該「債」的「程度」甚至要高於保留「重覆程式碼」所產生的量。

在筆者以往的經驗中,「重覆程式碼」是相當糟糕的一件事,將一段代碼「複製」後,並粗暴地「黏貼」在其它地方,使同樣的程式碼出現同一個專案中的兩處,甚至是多處,這行為無疑是撰寫程式碼時的「禁忌」,不少的前輩都告誡我們應該要盡量的避免此種行為;譬如耳熟能詳的「DRY」原則就是其中之一,其全文為「Don’t repeat yourself.」,也就是在告訴我們,「不要」重覆程式碼,這是因爲「重覆程式碼」不僅會讓程式碼變得冗長,又由於相同的程式邏輯散佈在專案的四處,所以還可能會導致「霰彈式修改(Shotgun Surgery)」情況的發生;也因此,在筆者的認知中,「重覆程式碼」一直�都是不應該被容許的。

但如今,忽然有人告訴我說:寧願接受「重覆程式碼」的存在,也不要冒著可能導致「錯誤的抽象」的風險;因此,這就不禁讓筆者好奇:什麼是「錯誤的抽象」,它又到底有多糟糕?

所以,今天我們就來談談,「Sandi Metz」口中的,「錯誤的抽象」。

正文

錯誤的抽象

什麼是「錯誤的抽象」?

在「The Wrong Abstraction」一文中,「Sandi Metz」舉了一個例子來解釋她所稱的「錯誤的抽象」,如下:

根據其內容的敘述,筆者認為,「Sandi Metz」所謂的「錯誤的抽象」,大概就是指一段「亂七八糟」且「邏輯不清」的「抽象」;而導致這現象的原因不外乎是「不同人共同開發」以及「過早的抽象」。

事實上,「Sandi Metz」所描述的現象,在軟體開發領域中,是一個相當常見的情況;尤其是「不同人共同開發」這件事,其幾乎無可避免;以軟體開發來說,多數的大型專案進行都是以「多人合作開發」的方式,即便是「獨立開發」,其也可能會因為不可抗拒的因素而會面臨到換人開發的情況,譬如人員流動,像是人力調度、離職⋯等;而「不同」的「開發者」自然存在一些差異,譬如「程度的落差」、「習慣的不同」,以及「思維的歧異」⋯等。

但是「不同人共同開發」並非無法解決,最常見的解決方式不外乎就是透過員工的「教育訓練」,以及制定完整地「開發規範」;此外,使用比較容易上手的技術框架,與建立完善的程式架構,也都能一定程度減少因為「多人合作開發」所造成的程式碼紊亂的問題。

除了「不同人共同開發」之外,「Sandi Metz」還有提到「過早的抽象」也是「錯誤的抽象」的成因之一;事實上,「過早的抽象」也的確是個惱人的議題,尤其是在專案開發時,開發人員通常是不會知曉專案的全貌,在如此情況下,若其冒然地進行架構設計,那麼就可能因為其對專案的不了解,而使得當下設計的程式架構無法滿足未來的使用,最後迫使我們必須為了因應未來的專案需求而對當前的程式架構進行「重構」,甚至是「疊床架屋」。

知名電腦科學家,「Donald Knuth」就曾說過:「過早的優化(Premature Optimization)」是萬惡的根源,更是導致專案「成本」大幅提高的主要兇手,其原文如下:

The real problem is that programmers have spent far too much time worrying about efficiency in the wrong places and at the wrong times; premature optimization is the root of all evil (or at least most of it) in programming.

真正的問題是程式設計師在錯誤的時間和地點花了太多的時間擔心效率問題;過早優化是程式設計中一切罪惡的根源(或至少是大部分罪惡的根源)。

因此,就有些人開始提倡應避免「過早的優化」的行為,譬如「過早的抽象」,其論點是:在某些情況下,我們應允許一定程度的「重覆程式碼」,即使這樣的方式可能會使得程式碼稍嫌「冗余」,但是它至少保持了程式碼碼的「簡單」、「直覺」;而該概念也正好符合「KISS」原則的概念,「KISS」是「Keep it simple, stupid.」的縮寫。

題外話,雖然「過早的優化」聽起來似乎有其有道理,但何謂「過早」,或著反過來問,到底什麼時候才是適合優化的時機呢?

對於這個問題,筆者認為「Martin Fowler」提倡的「三次重構原則(Rule of Three)」或許就是個相當不錯的選擇,它毫無疑問地是個相當簡單、直接,且容易用於判斷「重覆程式碼」是否該「重構��」的標準,詳見其著作:「Refactoring: Improving the Design of Existing Code」;「三次重構原則」的全文為:「Three strikes and you refactor.」;簡單的說,就是「重覆三次」,就重構。

但「三次重構原則」並不是絕對的,事實上,筆者覺得所謂「重構」的「最佳時機」,是會因為其專案特性、團隊習慣⋯等因素的差異而有不同的;但在毫無頭緒時,「三次重構原則」就是一個很不錯的選項。

關於「過早的優化」的議題,未來倘若有機會,筆者會再另闢篇幅,現在,我們先焦點放回「錯誤的抽象」上;從「Sandi Metz」的描述中,我們可以得知,她認為「過早的抽象」是「錯誤的抽象」的成因之一,而「錯誤的抽象」會造成比「重覆程式碼」更多的「技術債」,所以「Sandi Metz」認為與其承擔因為「錯誤的抽象」而可能會產生的代價,不如直接接受「重覆程式碼」。

上述這段話乍聽之下很合理,但不知道大家有沒有察覺出一個問題?

到底是「過早的抽象」導致了「錯誤的抽象」的產生,還是「過早的抽象」經過多次「疊床架屋」的改動後,才造成「錯誤的抽象」?

其兩者並不應該混為一談,就如同「Jason Swett」在「Why I don’t buy “duplication is cheaper than the wrong abstraction”」一文中的描述,「Jason Swett」認為,「Sandi Metz」所稱的「錯誤的抽象」就只是「壞程式碼(Bad Code)」的「代名詞」而已,他說道,如果「錯誤的抽象」是一段本來就「亂七八糟、邏輯不清」的「壞程式碼」,那麽,無關它「抽象化」與否,它都只是「壞程式��碼」,其,原文如下:

對於這個觀點,筆者其實是比較認同的。

就筆者的角度而言,我並不認為「錯誤的抽象」是「過早的抽象」的「果」;「錯誤的抽象」應該是「疊床架屋」的「果」,是「開發人員」沒有「不斷迭代」的「果」。

事實上,「優化」這件事在「軟體開發」的整個過程中,其應該都是一項持續進行的事情;我們應該在其尚未「亂七八糟、邏輯不清」前,就去「重構」;而不是等到其變成一團「混亂」時,再稱呼它為「錯誤的抽象」。

或許有人會說,持續地重構會造成相當的「技術債」,尤其在某些情況下,譬如缺乏完整的自動化測試,又或是既有的架構不夠彈性、既有代碼的耦合度過高;當然,也可能是「程式碼不熟悉」,譬如在多人開發的情況下,沒有了解合作夥伴們所撰寫的內容。

但就如同「Jason Swett」所說,不論程式人員不願「重構」的理由是什麼;但當該情況發生時,我們的處理方式應該是解決問題的根源,譬如,補上測試代碼,或是基於合理條件下改動原有架構、建立程式碼審查的制度;但絕對不是允許「重覆的程式碼」。

接著,我們簡單的討論一下,應該如何看待「重覆的程式碼」。

若以筆者的觀點來看,筆者不認為「重覆的程式碼」是完全不能允許存在的;事實上,筆者的觀念都是:基於某些前提下,「重覆程式碼」並不一定都是糟糕的,是可被接受的。

但這與「Sandi Metz」的「錯誤的抽象」的出發點是不同的;在筆者的認知裡,「優化」是一件持續發生的過程,我們應該不斷地「重構」,不論是在「開發時期」,亦或是「維護時期」,在專案中,只要需要,我們就應該將之「迭代」;而不是放任其發展到「亂七八糟、邏輯不清」時,再將責任推到「過早的抽象」。

筆者曾經聽過一句話,相當的認同,他說,「程式的設計是必然的,但是不能因為擔心專案需求會改動,就乾脆不做程式設計,事實上,沒有設計本身就是最糟糕的設計。」;事實上,我們要做的是,當我們發現目前的程式架構不敷當前需求使用時,我們就應該將之重構,而不是為貪圖方便而疊床架屋之。

同理,我們也可以將上述那段話換成「抽象化」,即「抽象化是必然的,但是不能因為擔心專案需求會改動,就乾脆不要抽象化。」。

抽象化

最後,筆者補充一些關於「抽象化」的議題,「抽象化」是「程式設計」中常見的一種手段,也是我們常用於「優化」程式碼的方式;此外,通常而言,「重構」是指「優化」程式碼的過程,但不見得都是將程式碼「抽象化」,亦可能為反向,如同「林信良」在「面對抽象雙面刃」中的敘述,如下:

其實「抽象化」一直都存在一些爭論,著名的「抽象滲漏原則(The Law of Leaky Abstractions)」就是其中之一,該原則是「Joel Spolsky」,詳見「The Law of Leaky Abstractions」或是「Joel on Software: And on Diverse and Occasionally Related Matters That Will Prove of Interest to Software Developers, Designers, and Managers, and to Those Who, Whether by Good Fortune or Ill Luck, Work with Them in Some Capacity」。

其事實上的“抽象化”一直都存在一些爭議,著名的“抽象漏原則(Leaky Abstractions Law)”就是其中之一,該原則是“Joel Spolsky”,詳見“ 《洩漏抽象原則》 ”或是“Joel 論軟體:以及軟體開發人員、設計人員和管理人員以及無論是幸運還是不幸,以某種身份與他們偶爾的人所感興趣的人所感興趣的人所感興趣。

此外,也可以參考「林信良」的「另眼看抽象滲漏」。

參考資料

- RailsConf 2014 — All the Little Things by Sandi Metz

RailsConf 2014 — Sandi Metz 撰寫的《所有小事》 - Sandi Metz, The Wrong Abstraction

Sandi Metz,《錯誤的抽象》 - Jason Swett, Why I don’t buy “duplication is cheaper than the wrong abstraction”

Jason Swett,為什麼我不相信“重複比錯誤的抽象更便宜” - Joel Spolsky, The Law of Leaky Abstractions

Joel Spolsky,《洩漏抽象定律》 - Joel Spolsky, Joel on Software: And on Diverse and Occasionally Related Matters That Will Prove of Interest to Software Developers, Designers, and Managers, and to Those Who, Whether by Good Fortune or Ill Luck, Work with Them in Some Capacity

Joel Spolsky,《Joel 論軟體:以及軟體開發人員、設計師和管理人員以及那些無論是幸運還是不幸,以某種身份與他們一起工作的人感興趣的各種偶爾相關的問題》 - Martin Fowler, Refactoring: Improving the Design of Existing Code

Martin Fowler,重構:改進現有程式碼的設計 - 林信良, 面對抽象雙面刃

- 林信良, 另眼看抽象滲漏

Law of Demeter

The Law of Demeter Creates More Problems Than It Solves

The Law of Demeter Creates More Problems Than It Solves

Most developers, when invoking the “Law of Demeter” or when pointing out a “Demeter Violation”, do so when a line of code has more than one dot: person.address.country.code. Like the near-pointless SOLID Principles, Demeter, too, suffers from making a vague claim that drives developers to myopically unhelpful behavior.

Writing SOLID is not Solid, I found the backstory and history of the principles really interesting. They were far flimsier than I had expected, and much more vague in their prescription. The problem was in their couching as “principles” and the overcomplex code that resulted from their oversimplification. Demeter is no different. It aims to help us manage coupling between classes, but when blindly applied to core classes and data structures, it leads to convoluted, over-de-coupled code that obscures behavior.

What is this Law of Demeter?

Update Jan 24, 2020: My former collegue Glenn Vanderburg pointed me to what he believes it he source of the “Law of Demeter”, which looks like a fax of the IEEE Software magazine in which it appears! It’s on the Universitatea Politehnica Timisoara’s website.

It does specifically mention object-oriented programming, and it states a few interesting things. First, it mentions pretty explicitly that they have no actual proof this law does what it says it does (maybe then don’t call it law? I dunno. That’s just me). Second, it presents a much more elaborate and nuanced definition than the paper linked below. The definitions of terms alone is almost a page long and somewhat dense.

Suffice it to say, I stand even more firm that this should not be called a “Law” and that the way most programmers understand by counting dots is absolutely wrong. This paper is hard to find and pretty hard to read (both due to its text, but also its presentation). I would be surprised if anyone invoking Demeter in a code review has read and understood it.

It’s hard to find a real source for the Law of Demeter, but the closest I could find is this page on Northeastern’s webstie, which says:

End of Update

This page on Northeastern’s webstie, summarizes the Law as stated in the paper above:

Each unit should have only limited knowledge about other units: only units “closely” related to the current unit.

The page then attempts to define “closely related”, which I will attempt to restate without the academic legalese:

- A unit is some method

methof a classClazz - Closely related units are classes that are:

- other methods of

Clazz. - passed into

methas arguments. - returned by other methods of

Clazz. - any instance variables of

Clazz.

Anything else should not be used by meth. So for example, if meth takes an argument arg, it’s OK to call a method other_meth on arg (arg.other_meth), but it’s not OK to call a method on that (arg.other_meth.yet_another_meth).

It’s also worth pointing out that this “Law” was not developed for the sake of object-oriented programming, but for help defining aspect-oriented programming, which you only tend to hear about in Java-land, and even then, not all that much.

That all said, this advice seems reasonable, but it does not really allow for nuance. Yes, we want to reduce coupling, but doing so has a cost (this is discussed at length in the book). In particular, it might be preferable for our code’s coupling to match that of the domain.

It also might be OK to be overly coupled to our language’s standard library or to the framework components of whatever framework we are using, since that coupling mimics the decision to be coupled to a language or framework.

Code Coupling can Mirror Domain Coupling

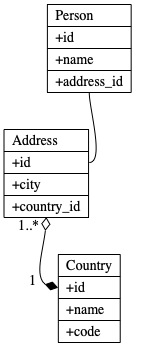

Consider this object model, where a person has an address, which has a country, which has a code.

Class diagram of the object model.

Suppose we have to write a method to figure out taxes based on country code of a person. Our method, determine_tax_method takes a Person as an argument. The basic logic is:

- If a person is in the US and a contractor, we don’t do tax determination.

- If they are in the US and not a contractor, we use the US-based tax determination, which requires a zipcode.

- If they are in the UK, we use the UK based determination, which requires a postcode.

- Otherwise, we don’t do tax determination.

Here’s what that might look like:

class TaxDetermination

def determine_tax_method(person)

case person.address.country.code

when "US"

if person.contractor?

NoTaxDetermination.new

else

USTaxDetermination.new(person.address.postcode)

end

when "UK"

UKTaxDetermination.new(person.address.postcode)

else

NoTaxDetermination.new

end

end

end

If address, country, and code are all methods, according to the Law of Demeter, we have created a violation, because we are depending on the class of an object returned by a method called on an argument. In this case, the return value of person.address is a Country and thus not a “closely related unit”.

But is that really true?

Person has a well-defined type. It is defined as having an address, which is an Address, another well-defined type. That has a country, well-defined in the Country class, which has a code attribute that returns a string. These aren’t objects to which we are sending messages, at least not semantically. These are data structures we are navigating to access data from our domain model. The difference is meaningful!

Even still, it’s hard to quantify the problems with a piece of code. The best way to evaluate a technique is to compare code that uses it to code that does not. So, let’s change our code so it doesn’t violate the Law of Demeter.

A common way to do this is to provide proxy methods on an allowed class to do the navigation for us:

class TaxDetermination

def determine_tax_method(person)

case person.country_code

# ^^^^^^^^^^^^

when "US"

if person.contractor?

NoTaxDetermination.new

else

USTaxDetermination.new(person.postcode)

# ^^^^^^^^

end

when "UK"

UKTaxDetermination.new(person.postcode)

# ^^^^^^^^

else

NoTaxDetermination.new

end

end

end

How do we implement country_code and postcode?

class Person

def country_code

self.address.country.code

end

def postcode

self.address.postcode

end

end

Of course, country_code now contains a Demeter Violation, because it calls a method on the return type of a closely related unit. Remember, self.address is allowed, and calling methods on self.address is allowed, but that’s it. Calling code on country is the violation. So…another proxy method.

class Person

def country_code

self.address.country_code

# ^^^^^^^^^^^^

end

end

class Address

def country_code

self.country.code

end

end

And now we comply with the Law of Demeter, but what have we actually accomplished? All of the methods we’ve been dealing with are really just attributes returning unfettered access to public members of a data structure.

We’ve added three new public API methods to two classes, all of which require tests, which means we’ve incurred both an opportunity cost in making them and a carrying cost in their continued existence.

We also now have two was to get a person’s country code, two ways to get their post code, and two was to get the country code of an address. It’s hard to see this as a benefit.

For classes that are really just data structures, especially when they are core domain concepts that drive the reason for our app’s existence, applying the Law of Demeter does more harm than good. And when you consider that most developers who apply it don’t read the backstory and simply count dots in lines of code, you end up with myopically overcomplex code with little demonstrable benefit.

But let’s take this one step further, shall we?

Violating Demeter by Depending on the Standard Library

Suppose we want to send physical mail to a person, but our carrier is a horrible legacy US-centric one that requires being given a first name and last name. We only collected full name, so we fake it out by looking for a space in the name. Anyone with no spaces in their names is handled manually by queuing their record to a customer service person via handle_manually.

class MailSending

def send_mailer(person)

fake_first_last = /^(?<first>\S+)\s(?<last>.*)$/

match_data = fake_first_last.match(person.name)

if match_data

legacy_carrier(match_data[:first], match_data[:last])

else

handle_manually(person)

end

end

end

This has a Demeter violation. A Regexp (created by the /../ literal) returns a MatchData if there is match. We can’t call methods on an object returned by one of our closely related units’ methods. We can call match on a Regexp, but we can’t call a method on what that returns. In this case, we’re calling [] on the returned MatchData. How do we eliminate this egregious problem?

We can’t make proxy methods for first name and last name in Person, because that method will have the same problem as this one (it also would put use-case specific methods on a core class, but that’s another problem). We really do need to both match a regexp and examine its results. But the Law does not allow for such subtly! We could create a proxy class for this parsing.

class LegacyFirstLastParser

FAKE_FIRST_LAST = /^(?<first>\S+)\s(?<last>.*)$/

def initialize(name)

@match_data = name.match(FAKE_FIRST_LAST)

end

def can_guess_first_last?

!@match_data.nil?

end

def first

@match_data[:first]

end

def last

@match_data[:last]

end

end

Now, we can use this class:

class MailSending

def send_mailer(person)

parser = LegacyFirstLastParser.new(person.name)

if parser.can_guess_first_last?

legacy_carrier(parser.first, parser.last)

else

handle_manually(person)

end

end

end

Hmm. LegacyFirstLastParser was just plucked out of the ether. It definitely is not a closely-related unit based on our definition. We’ll need to create that via some sort of private method:

class MailSending

def send_mailer(person)

parser = legacy_first_last_parser(person.name)

# ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

if parser.can_guess_first_last?

legacy_carrier(parser.first, parser.last)

else

handle_manually(person)

end

end

private

def legacy_first_last_parser(name)

LegacyFirstLastParser.new(name)

end

end

Of course, legacy_first_last_parser has the same problem as send_mailer, in that it pulls LegacyFirstLastParser out of thin air. This means that MailSending has to be given the class, so let’s invert those dependencies:

class MailSending

def initialize(legacy_first_last_parser_class)

@legacy_first_last_parser_class = legacy_first_last_parser_class

end

def send_mailer(person)

parser = legacy_first_last_parser(person.name)

if parser.can_guess_first_last?

legacy_carrier(parser.first, parser.last)

else

handle_manually(person)

end

end

private

def legacy_first_last_parser(name)

@legacy_first_last_parser_class.new(name)

end

end

This change now requires changing every single use of the MailSending class to pass in the LegacyFirstLastParser class. Sigh.

Is this all better code? Should we have not done this because Regexp and MatchData are in the standard library? The Law certainly doesn’t make that clear.

Just as with all the various SOLID Principles, we really should care about keeping the coupling of our classes low and the cohesion high, but no Law is going to guide is to the right decision, because it lacks subtly and nuance. It also doesn’t provide much help once we have a working understanding of coupling and cohesion. When a team aligns on what those mean, code can discussed directly—you don’t need a Law to help have that discussion and, in fact, talking about it is a distraction.

Suppose we kept our discussion of send_mailer to just coupling. It’s pretty clear that coupling to the language’s standard library is not a real problem. We’ve chosen Ruby, switching programming languages would be a total rewrite, so coupling to Ruby’s standard library is fine and good.

Consider discussing coupling around determine_tax_method. We might have decided that since people, addresses, and countries are central concepts in our app, code that’s coupled to them and their interrelationship is generally OK. If these concepts are stable, coupling to them doesn’t have a huge downside. And the domain should be stable.

Damn the Law.

Goodbye, Clean Code

Goodbye, Clean Code, dan abramov

Repeat yourself, do more than one thing, and rewrite everything

It was a late evening.

My colleague has just checked in the code that they’ve been writing all week. We were working on a graphics editor canvas, and they implemented the ability to resize shapes like rectangles and ovals by dragging small handles at their edges.

The code worked.

But it was repetitive. Each shape (such as a rectangle or an oval) had a different set of handles, and dragging each handle in different directions affected the shape’s position and size in a different way. If the user held Shift, we’d also need to preserve proportions while resizing. There was a bunch of math.

The code looked something like this:

let Rectangle = {

resizeTopLeft(position, size, preserveAspect, dx, dy) {

// 10 repetitive lines of math

},

resizeTopRight(position, size, preserveAspect, dx, dy) {

// 10 repetitive lines of math

},

resizeBottomLeft(position, size, preserveAspect, dx, dy) {

// 10 repetitive lines of math

},

resizeBottomRight(position, size, preserveAspect, dx, dy) {

// 10 repetitive lines of math

},

};

let Oval = {

resizeLeft(position, size, preserveAspect, dx, dy) {

// 10 repetitive lines of math

},

resizeRight(position, size, preserveAspect, dx, dy) {

// 10 repetitive lines of math

},

resizeTop(position, size, preserveAspect, dx, dy) {

// 10 repetitive lines of math

},

resizeBottom(position, size, preserveAspect, dx, dy) {

// 10 repetitive lines of math

},

};

let Header = {

resizeLeft(position, size, preserveAspect, dx, dy) {

// 10 repetitive lines of math

},

resizeRight(position, size, preserveAspect, dx, dy) {

// 10 repetitive lines of math

},

}

let TextBlock = {

resizeTopLeft(position, size, preserveAspect, dx, dy) {

// 10 repetitive lines of math

},

resizeTopRight(position, size, preserveAspect, dx, dy) {

// 10 repetitive lines of math

},

resizeBottomLeft(position, size, preserveAspect, dx, dy) {

// 10 repetitive lines of math

},

resizeBottomRight(position, size, preserveAspect, dx, dy) {

// 10 repetitive lines of math

},

};

That repetitive math was really bothering me.

It wasn’t clean.

Most of the repetition was between similar directions. For example, Oval.resizeLeft() had similarities with Header.resizeLeft(). This was because they both dealt with dragging the handle on the left side.

The other similarity was between the methods for the same shape. For example, Oval.resizeLeft() had similarities with the other Oval methods. This was because they all dealt with ovals. There was also some duplication between Rectangle, Header, and TextBlock because text blocks were rectangles.

I had an idea.

We could remove all duplication by grouping the code like this instead:

let Directions = {

top(...) {

// 5 unique lines of math

},

left(...) {

// 5 unique lines of math

},

bottom(...) {

// 5 unique lines of math

},

right(...) {

// 5 unique lines of math

},

};

let Shapes = {

Oval(...) {

// 5 unique lines of math

},

Rectangle(...) {

// 5 unique lines of math

},

}

and then composing their behaviors:

let Directions = {

top(...) {

// 5 unique lines of math

},

left(...) {

// 5 unique lines of math

},

bottom(...) {

// 5 unique lines of math

},

right(...) {

// 5 unique lines of math

},

};

let Shapes = {

Oval(...) {

// 5 unique lines of math

},

Rectangle(...) {

// 5 unique lines of math

},

}

The code is half the total size, and the duplication is gone completely! So clean. If we want to change the behavior for a particular direction or a shape, we could do it in a single place instead of updating methods all over the place.

It was already late at night (I got carried away). I checked in my refactoring to master and went to bed, proud of how I untangled my colleague’s messy code.

The Next Morning

… did not go as expected.

My boss invited me for a one-on-one chat where they politely asked me to revert my change. I was aghast. The old code was a mess, and mine was clean!

I begrudgingly complied, but it took me years to see they were right.

It’s a Phase

Obsessing with “clean code” and removing duplication is a phase many of us go through. When we don’t feel confident in our code, it is tempting to attach our sense of self-worth and professional pride to something that can be measured. A set of strict lint rules, a naming schema, a file structure, a lack of duplication.

You can’t automate removing duplication, but it does get easier with practice. You can usually tell whether there’s less or more of it after every change. As a result, removing duplication feels like improving some objective metric about the code. Worse, it messes with people’s sense of identity: “I’m the kind of person who writes clean code”. It’s as powerful as any sort of self-deception.

Once we learn how to create abstractions, it is tempting to get high on that ability, and pull abstractions out of thin air whenever we see repetitive code. After a few years of coding, we see repetition everywhere — and abstracting is our new superpower. If someone tells us that abstraction is a virtue, we’ll eat it. And we’ll start judging other people for not worshipping “cleanliness”.

I see now that my “refactoring” was a disaster in two ways:

- Firstly, I didn’t talk to the person who wrote it. I rewrote the code and checked it in without their input. Even if it was an improvement (which I don’t believe anymore), this is a terrible way to go about it. A healthy engineering team is constantly building trust. Rewriting your teammate’s code without a discussion is a huge blow to your ability to effectively collaborate on a codebase together.

- Secondly, nothing is free. My code traded the ability to change requirements for reduced duplication, and it was not a good trade. For example, we later needed many special cases and behaviors for different handles on different shapes. My abstraction would have to become several times more convoluted to afford that, whereas with the original “messy” version such changes stayed easy as cake.

Am I saying that you should write “dirty” code? No. I suggest to think deeply about what you mean when you say “clean” or “dirty”. Do you get a feeling of revolt? Righteousness? Beauty? Elegance? How sure are you that you can name the concrete engineering outcomes corresponding to those qualities? How exactly do they affect the way the code is written and modified?

I sure didn’t think deeply about any of those things. I thought a lot about how the code looked — but not about how it evolved with a team of squishy humans.

Coding is a journey. Think how far you came from your first line of code to where you are now. I reckon it was a joy to see for the first time how extracting a function or refactoring a class can make convoluted code simple. If you find pride in your craft, it is tempting to pursue cleanliness in code. Do it for a while.

But don’t stop there. Don’t be a clean code zealot. Clean code is not a goal. It’s an attempt to make some sense out of the immense complexity of systems we’re dealing with. It’s a defense mechanism when you’re not yet sure how a change would affect the codebase but you need guidance in a sea of unknowns.

Let clean code guide you. Then let it go.

Repeat yourself

Repeat yourself, do more than one thing, and rewrite everything

Repeat yourself, do more than one thing, and rewrite everything

If you ask a programmer for advice—a terrible idea—they might tell you something like the following: Don’t repeat yourself. Programs should do one thing and one thing well. Never rewrite your code from scratch, ever!.

Following “Don’t Repeat Yourself” might lead you to a function with four boolean flags, and a matrix of behaviours to carefully navigate when changing the code. Splitting things up into simple units can lead to awkward composition and struggling to coordinate cross cutting changes. Avoiding rewrites means they’re often left so late that they have no chance of succeeding.

The advice isn’t inherently bad—although there is good intent, following it to the letter can create more problems than it promises to solve.

Sometimes the best way to follow an adage is to do the exact opposite: embrace feature switches and constantly rewrite your code, pull things together to make coordination between them easier to manage, and repeat yourself to avoid implementing everything in one function..

This advice is much harder to follow, unfortunately.

“Don’t Repeat Yourself” is almost a truism—if anything, the point of programming is to avoid work.

No-one enjoys writing boilerplate. The more straightforward it is to write, the duller it is to summon into a text editor. People are already tired of writing eight exact copies of the same code before even having to do so. You don’t need to convince programmers not to repeat themselves, but you do need to teach them how and when to avoid it.

“Don’t Repeat Yourself” often gets interpreted as “Don’t Copy Paste” or to avoid repeating code within the codebase, but the best form of avoiding repetition is in avoiding reimplementing what exists elsewhere—and thankfully most of us already do!

Almost every web application leans heavily on an operating system, a database, and a variety of other lumps of code to get the job done. A modern website reuses millions of lines of code without even trying. Unfortunately, programmers love to avoid repetition, and “Don’t Repeat Yourself” turns into “Always Use an Abstraction”.

By an abstraction, I mean two interlinked things: a idea we can think and reason about, and the way in which we model it inside our programming languages. Abstractions are way of repeating yourself, so that you can change multiple parts of your program in one place. Abstractions allow you to manage cross-cutting changes across your system, or sharing behaviors within it.

The problem with always using an abstraction is that you’re preemptively guessing which parts of the codebase need to change together. “Don’t Repeat Yourself” will lead to a rigid, tightly coupled mess of code. Repeating yourself is the best way to discover which abstractions, if any, you actually need.

As Sandi Metz put it, “duplication is far cheaper than the wrong abstraction”.

You can’t really write a re-usable abstraction up front. Most successful libraries or frameworks are extracted from a larger working system, rather than being created from scratch. If you haven’t built something useful with your library yet, it is unlikely anyone else will. Code reuse isn’t a good excuse to avoid duplicating code, and writing reusable code inside your project is often a form of preemptive optimization.

When it comes to repeating yourself inside your own project, the point isn’t to be able to reuse code, but rather to make coordinated changes. Use abstractions when you’re sure about coupling things together, rather than for opportunistic or accidental code reuse—it’s ok to repeat yourself to find out when.

Repeat yourself, but don’t repeat other people’s hard work. Repeat yourself: duplicate to find the right abstraction first, then deduplicate to implement it.

With “Don’t Repeat Yourself”, some insist that it isn’t about avoiding duplication of code, but about avoiding duplication of functionality or duplication of responsibility. This is more popularly known as the “Single Responsibility Principle”, and it’s just as easily mishandled.

Gather responsibilities to simplify interactions between them

When it comes to breaking a larger service into smaller pieces, one idea is that each piece should only do one thing within the system—do one thing, and do it well—and the hope is that by following this rule, changes and maintenance become easier.

It works out well in the small: reusing variables for different purposes is an ever-present source of bugs. It’s less successful elsewhere: although one class might do two things in a rather nasty way, disentangling it isn’t of much benefit when you end up with two nasty classes with a far more complex mess of wiring between them.

The only real difference between pushing something together and pulling something apart is that some changes become easier to perform than others.

The choice between a monolith and microservices is another example of this—the choice between developing and deploying a single service, or composing things out of smaller, independently developed services.

The big difference between them is that cross-cutting change is easier in one, and local changes are easier in the other. Which one works best for a team often depends more on environmental factors than on the specific changes being made.

Although a monolith can be painful when new features need to be added and microservices can be painful when co-ordination is required, a monolith can run smoothly with feature flags and short lived branches and microservices work well when deployment is easy and heavily automated.

Even a monolith can be decomposed internally into microservices, albeit in a single repository and deployed as a whole. Everything can be broken into smaller parts—the trick is knowing when it’s an advantage to do so.

Modularity is more than reducing things to their smallest parts.

Invoking the ‘single responsibility principle’, programmers have been known to brutally decompose software into a terrifyingly large number of small interlocking pieces—a craft rarely seen outside of obscenely expensive watches, or bash.

The traditional UNIX command line is a showcase of small components that do exactly one function, and it can be a challenge to discover which one you need and in which way to hold it to get the job done. Piping things into awk '{print $2}' is almost a rite of passage.

Another example of the single responsibility principle is git. Although you can use git checkout to do six different things to the repository, they all use similar operations internally. Despite having singular functionality, components can be used in very different ways.

A layer of small components with no shared features creates a need for a layer above where these features overlap, and if absent, the user will create one, with bash aliases, scripts, or even spreadsheets to copy-paste from.

Even adding this layer might not help you: git already has a notion of user-facing and automation-facing commands, and the UI is still a mess. It’s always easier to add a new flag to an existing command than to it is to duplicate it and maintain it in parallel.

Similarly, functions gain boolean flags and classes gain new methods as the needs of the codebase change. In trying to avoid duplication and keep code together, we end up entangling things.

Although components can be created with a single responsibility, over time their responsibilities will change and interact in new and unexpected ways. What a module is currently responsible for within a system does not necessarily correlate to how it will grow.

Modularity is about limiting the options for growth

A given module often gets changed because it is the easiest module to change, rather than the best place for the change to be made. In the end, what defines a module is what pieces of the system it will never responsible for, rather what it is currently responsible for.

When a unit has no rules about what code cannot be included, it will eventually contain larger and larger amounts of the system. This is eternally true of every module named ‘util’, and why almost everything in a Model-View-Controller system ends up in the controller.

In theory, Model-View-Controller is about three interlocking units of code. One for the database, another for the UI, and one for the glue between them. In practice, Model-View-Controller resembles a monolith with two distinct subsystems—one for the database code, another for the UI, both nestled inside the controller.

The purpose of MVC isn’t to just keep all the database code in one place, but also to keep it away from frontend code. The data we have and how we want to view it will change over time independent of the frontend code.

Although code reuse is good and smaller components are good, they should be the result of other desired changes. Both are tradeoffs, introducing coupling through a lack of redundancy, or complexity in how things are composed. Decomposing things into smaller parts or unifying them is neither universally good nor bad for the codebase, and largely depends on what changes come afterwards.

In the same way abstraction isn’t about code reuse, but coupling things for change, modularity isn’t about grouping similar things together by function, but working out how to keep things apart and limiting co-ordination across the codebase.

This means recognizing which bits are slightly more entangled than others, knowing which pieces need to talk to each other, which need to share resources, what shares responsibilities, and most importantly, what external constraints are in place and which way they are moving.

In the end, it’s about optimizing for those changes—and this is rarely achieved by aiming for reusable code, as sometimes handling changes means rewriting everything.

Rewrite Everything

Usually, a rewrite is only a practical option when it’s the only option left. Technical debt, or code the seniors wrote that we can’t be rude about, accrues until all change becomes hazardous. It is only when the system is at breaking point that a rewrite is even considered an option.

Sometimes the reasons can be less dramatic: an API is being switched off, a startup has taken a beautiful journey, or there’s a new fashion in town and orders from the top to chase it. Rewrites can happen to appease a programmer too—rewarding good teamwork with a solo project.

The reason rewrites are so risky in practice is that replacing one working system with another is rarely an overnight change. We rarely understand what the previous system did—many of its properties are accidental in nature. Documentation is scarce, tests are ornamental, and interfaces are organic in nature, stubbornly locking behaviors in place.

If migrating to the replacement depends on switching over everything at once, make sure you’ve booked a holiday during the transition, well in advance.

Successful rewrites plan for migration to and from the old system, plan to ease in the existing load, and plan to handle things being in one or both places at once. Both systems are continuously maintained until one of them can be decommissioned. A slow, careful migration is the only option that reliably works on larger systems.

To succeed, you have to start with the hard problems first—often performance related—but it can involve dealing with the most difficult customer, or biggest customer or user of the system too. Rewrites must be driven by triage, reducing the problem in scope into something that can be effectively improved while being guided by the larger problems at hand.

If a replacement isn’t doing something useful after three months, odds are it will never do anything useful.

The longer it takes to run a replacement system in production, the longer it takes to find bugs. Unfortunately, migrations get pushed back in the name of feature development. A new project has the most room for feature bloat—this is known as the second-system effect.

The second system effect is the name of the canonical doomed rewrite, one where numerous features are planned, not enough are implemented, and what has been written rarely works reliably. It’s a similar to writing a game engine without a game to implement to guide decisions, or a framework without a product inside. The resulting code is an unconstrained mess that is barely fit for its purpose.

The reason we say “Never Rewrite Code” is that we leave rewrites too late, demand too much, and expect them to work immediately. It’s more important to never rewrite in a hurry than to never rewrite at all.

null is true, everything is permitted

The problem with following advice to the letter is that it rarely works in practice. The problem with following it at all costs is that eventually we cannot afford to do so.

It isn’t “Don’t Repeat Yourself”, but “Some redundancy is healthy, some isn’t”, and using abstractions when you’re sure you want to couple things together.

It isn’t “Each thing has a unique component”, or other variants of the single responsibility principle, but “Decoupling parts into smaller pieces is often worth it if the interfaces are simple between them, and try to keep the fast changing and tricky to implement bits away from each other”.

It’s never “Don’t Rewrite!”, but “Don’t abandon what works”. Build a plan for migration, maintain in parallel, then decommission, eventually. In high-growth situations you can probably put off decommissioning, and possibly even migrations.

When you hear a piece of advice, you need to understand the structure and environment in place that made it true, because they can just as often make it false. Things like “Don’t Repeat Yourself” are about making a tradeoff, usually one that’s good in the small or for beginners to copy at first, but hazardous to invoke without question on larger systems.

In a larger system, it’s much harder to understand the consequences of our design choices—in many cases the consequences are only discovered far, far too late in the process and it is only by throwing more engineers into the pit that there is any hope of completion.

In the end, we call our good decisions ‘clean code’ and our bad decisions ‘technical debt’, despite following the same rules and practices to get there.

丟給語言模型翻譯

重複自己,做超過一件事,並且重寫所有內容

如果你向工程師尋求建議——這是個糟糕的主意——他們可能會告訴你類似這樣的話:不要重複自己;程式應該只做好一件事;永遠不要從頭重寫你的程式碼。

遵循「不要重複自己」可能會導致你寫出一個帶有四個布林值標記的函數,並且在修改程式碼時需要小心地處理各種行為的組合。將事情分割成簡單的單元可能會導致尷尬的組合,並且難以協調交叉性的更改。避免重寫意味著它們經常被拖延到很晚,以至於沒有成功的機會。

這些建議本身並不壞——儘管出發點是好的,但完全照字面意思執行可能會造成比它承諾解決的更多問題。

有時候遵循一個格言的最佳方式是做完全相反的事:擁抱功能開關並持續重寫你的程式碼,將事物整合在一起使它們之間的協調更容易管理,並且重複自己以避免在一個函數中實現所有功能。

不幸的是,這個建議更難遵循。

重複自己以發現抽象化

「不要重複自己」幾乎是一個自明之理——如果說有什麼的話,程式設計的重點就是避免重複工作。

沒有人喜歡寫樣板程式碼。寫起來越直接,在文字編輯器中敲打出來就越無聊。人們在還沒開始寫之前就已經厭倦了寫出完全相同程式碼的八個副本。你不需要說服工程師不要重複自己,但你確實需要教導他們如何以及何時避免它。

「不要重複自己」經常被解釋為「不要複製貼上」或避免在程式碼庫中重複程式碼,但避免重複的最佳形式是避免重新實現已經存在於其他地方的東西——而且幸運的是,我們大多數人已經在這樣做了!

幾乎每個網路應用程式都heavily依賴作業系統、資料庫和各種其他程式碼來完成工作。現代網站在不經意間就重複使用了數百萬行程式碼。不幸的是,工程師喜歡避免重複,而「不要重複自己」變成了「總是使用抽象化」。

說到抽象化,我指的是兩個相互關聯的事物:一個我們可以思考和推理的概念,以及我們在程式語言中對它建模的方式。抽象化是一種重複自己的方式,這樣你就可以在一個地方更改程式的多個部分。抽象化允許你管理系統中的交叉性更改,或在其中共享行為。

總是使用抽象化的問題在於,你在預先猜測程式碼庫的哪些部分需要一起更改。「不要�重複自己」將導致一個僵硬的、緊密耦合的程式碼混亂。重複自己是發現你實際需要哪些抽象化(如果有的話)的最佳方式。

正如Sandi Metz所說:「重複遠比錯誤的抽象化便宜」。

你實際上無法預先寫出一個可重用的抽象化。大多數成功的函式庫或框架都是從一個更大的運作中的系統中提取出來的,而不是從頭開始創建的。如果你還沒有用你的函式庫構建出有用的東西,其他人也不太可能會用它。程式碼重用不是避免重複程式碼的好藉口,而且在你的專案中寫可重用的程式碼通常是一種過早優化的形式。

當涉及到在你自己的專案中重複自己時,重點不是能夠重用程式碼,而是進行協調性的更改。在你確定要將事物耦合在一起時使用抽象化,而不是為了機會主義或意外的程式碼重用——重複自己以找出何時需要這樣做是可以的。

重複自己,但不要重複其他人的辛勤工作。重複自己:首先重複以找到正確的抽象化,然後去除重複以實現它。

關於「不要重複自己」,有些人堅持認為這不是關於避免程式碼重複,而是關於避免功能重複或責任重複。這更普遍地被稱為「單一責任原則」,而且同樣容易被誤解。

匯聚責任以簡化其之間的互動

當談到將大型服務拆分成小塊時,一種想法是系統中的每個部分應該只做一件事——做好一件事——希望通過遵循這個規則,變更和維護會變得更容易。

這在小範圍內運作良好:將變數用於不同目的是一個永恆存在的錯誤來源。在其他地方就不那麼成功了:儘管一個類可能以相當糟糕的方式做兩件事,但當你最終得到兩個糟糕的類,它們之間有著更複雜的連接混亂時,解開它並沒有多大好處。

將事物推到一起和將事物分開的唯一真正區別是,某些更改變��得比其他更改更容易執行。

整體架構和微服務之間的選擇是另一個例子——在開發和部署單一服務,或是由較小的、獨立開發的服務組成的選擇之間。

它們之間的最大區別是,在一個中進行交叉性更改更容易,而在另一個中進行局部更改更容易。哪一個最適合團隊通常更多地取決於環境因素,而不是正在進行的具體更改。

儘管當需要添加新功能時,整體架構可能會很痛苦,而當需要協調時,微服務可能會很痛苦,但整體架構可以通過功能標記和短期分支順利運行,而當部署容易且高度自動化時,微服務也能很好地工作。

即使是整體架構也可以在內部分解為微服務,儘管是在單一儲存庫中並作為一個整體部署。所有事物都可以被分解成更小的部分——訣竅是知道何時這樣做是有利的。

模組化不僅僅是將事物減少到最小的部分

援引「單一責任原則」,工程師已知會殘酷地將軟體分解成驚人數量的小型互鎖部件——這種工藝很少在昂貴的手錶或bash之外見到。

傳統的UNIX命令列展示了只執行一個功能的小型元件,要發現你需要哪一個以及如何使用它來完成工作可能是一個挑戰。將東西導入到 awk '{print $2}' 幾乎是一種成年禮。

git是單一責任原則的另一個例子。儘管你可以使用git checkout對儲存庫做六種不同的事情,但它們在內部都使用類似的操作。儘管具有單一功能,元件可以以非常不同的方式使用。

沒有共享功能的小型元件層創造了對上層的需求,這些功能在這裡重疊,如果缺乏,使用者將創建一個,通過bash別名、腳本,甚至是用於複製粘貼的電子表格。

即使添加這一層可能也幫不了你:git已經有了面向使用者和面向自動化的命令的概念,但UI仍然是一團糟。為現�有命令添加新標記總是比複製它並平行維護更容易。

同樣,隨著程式碼庫需求的變化,函數獲得布林值標記,類獲得新方法。在試圖避免重複並將程式碼放在一起時,我們最終將事物糾纏在一起。

儘管元件可以用單一責任創建,但隨著時間推移,它們的責任將以新的和意想不到的方式改變和互動。模組目前在系統中負責的內容不一定與它將如何發展相關。

模組化是關於限制增長的選項

給定的模組經常被更改,因為它是最容易更改的模組,而不是進行更改的最佳位置。最終,定義模組的是系統中它永遠不會負責的部分,而不是它目前負責的部分。

當一個單元對不能包含什麼程式碼沒有規則時,它最終將包含越來越多的系統。這對於每個名為'util'的模組來說永遠是真實的,這也是為什麼在Model-View-Controller系統中幾乎所有東西最終都在控制器中。

理論上,Model-View-Controller是關於三個互鎖的程式碼單元。一個用於資料庫,另一個用於UI,還有一個用於它們之間的粘合劑。在實踐中,Model-View-Controller類似於具有兩個不同子系統的整體架構——一個用於資料庫程式碼,另一個用於UI,兩者都嵌套在控制器內。

MVC的目的不僅僅是將所有資料庫程式碼放在一個地方,還要將它遠離前端程式碼。我們擁有的資料以及我們想要查看它的方式將隨時間獨立於前端程式碼而改變。

儘管程式碼重用是好的,較小的元件也是好的,但它們應該是其他期望變更的結果。兩者都是權衡,通過缺乏冗餘引入耦合,或在事物如何組合方面引入複雜性。將事物分解成更小的部分或統一它們對程式碼庫來說既不是普遍好也不是普遍壞,很大程度上取決於之後會發生什麼變化。

就像抽象化不是關於程式碼重用,而是�為了變更而耦合事物一樣,模組化不是關於按功能將相似的事物組合在一起,而是找出如何讓事物分開並限制整個程式碼庫的協調。

這意味著要認識哪些部分比其他部分稍微更糾纏,知道哪些部分需要相互溝通,哪些需要共享資源,什麼共享責任,最重要的是,存在什麼外部約束以及它們向哪個方向移動。

最終,這是關於為這些變更優化——這很少通過追求可重用的程式碼來實現,因為有時處理變更意味著重寫所有內容。

重寫一切

通常,重寫只有在成為唯一選擇時才是實際可行的選項。技術債務,或是我們不能無禮評論的資深工程師寫的程式碼,累積到所有更改都變得危險。只有當系統到達臨界點時,重寫才會被考慮為一個選項。

有時原因可能不那麼戲劇性:一個API被關閉了,一個新創公司完成了美好的旅程,或者城裡有了新的時尚潮流和上級追逐它的命令。重寫也可能發生在安撫工程師時——用一個單獨的專案來獎勵良好的團隊合作。

重寫在實踐中如此冒險的原因是,用另一個系統替換一個運作中的系統很少是一夜之間的改變。我們很少理解先前的系統做了什麼——它的許多特性本質上是偶然的。文檔稀少,測試是裝飾性的,介面本質上是有機的,頑固地將行為鎖定在適當的位置。

如果遷移到替代系統取決於一次性切換所有內容,請確保你提前預訂了過渡期間的假期。

成功的重寫會計劃新舊系統間的遷移,計劃逐步增加現有負載,並計劃處理事物同時存在於一個或兩個地方的情況。兩個系統都持續維護,直到其中一個可以被停用。在較大的系統上,緩慢、謹慎的遷移是唯一可靠的選擇。

要成功,你必須先從困難的問題開始——通常與性能相關——但也可能涉及處理最困難的客戶,或系統最大的客戶或使用者。重寫必須由分類驅動,將問題範圍縮小到可以有效改進的程度,同時由當前的更大問題引導。

如果替換系統在三個月後仍然沒有做出任何有用的事情,那麼它很可能永遠不會做出任何有用的事情。

在生產環境中運行替換系統所需的時間越長,找到錯誤所需的時間就越長。不幸的是,遷移因功能開發而被推遲。新專案有最多的功能膨脹空間——這被稱為第二系統效應。

第二系統效應是典型的注定失敗的重寫的名稱,其中計劃了大量功能,實現的不夠多,而且已經寫好的很少能可靠工作。這類似於在沒有遊戲來指導決策的情況下寫遊戲引擎,或在沒有內部產品的情況下寫框架。結果的程式碼是一個無約束的混亂,幾乎不適合其目的。

我們說「永遠不要重寫程式碼」的原因是我們把重寫留得太晚,要求太多,並期望它們立即工作。永遠不要倉促重寫比完全不重寫更重要。

空值為真,一切皆允許

完全按照建議行事的問題是它在實踐中很少有效。不惜一切代價遵循它的問題是,最終我們無法承擔這樣做的代價。

它不是「不要重複自己」,而是「一些冗餘是健康的,一些不是」,並且在你確定想要將事物耦合在一起時使用抽象化。

它不是「每個事物都有一個獨特的組件」,或單一責任原則的其他變體,而是「如果介面之間簡單,將部分解耦成更小的部分通常是值得的,並試圖讓快速變化和難以實現的部分彼此遠離」。

它永遠不是「不要重寫!」,而是「不要放棄正在工作的東西」。建立遷移計劃,並行維護,然後最終停用。在高速增長的情況下,你可能可以推遲停用,甚至可能推遲遷移。

當你聽到一個建議時,你需要理解使它成為真理的結構和環��境,因為它們同樣經常使它成為假的。像「不要重複自己」這樣的事情是關於做出權衡,通常在小範圍內或對初學者來說一開始複製是好的,但在較大的系統上不加質疑地調用是危險的。

在較大的系統中,理解我們的設計選擇的後果要困難得多——在許多情況下,這些後果只有在過程中太晚太晚時才被發現,只有通過將更多的工程師投入坑中才有完成的希望。

最終,我們將我們的好決定稱為「乾淨的程式碼」,將壞決定稱為「技術債務」,儘管遵循相同的規則和實踐來達到那裡。

Easy to Debug

Write code that’s easy to delete, and easy to debug too

Write code that’s easy to delete, and easy to debug too

Debuggable code is code that doesn’t outsmart you. Some code is a little to harder to debug than others: code with hidden behaviour, poor error handling, ambiguity, too little or too much structure, or code that’s in the middle of being changed. On a large enough project, you’ll eventually bump into code that you don’t understand.

On an old enough project, you’ll discover code you forgot about writing—and if it wasn’t for the commit logs, you’d swear it was someone else. As a project grows in size it becomes harder to remember what each piece of code does, harder still when the code doesn’t do what it is supposed to. When it comes to changing code you don’t understand, you’re forced to learn about it the hard way: Debugging.

Writing code that’s easy to debug begins with realising you won’t remember anything about the code later.

Many used methodology salesmen have argued that the way to write understandable code is to write clean code. The problem is that “clean” is highly contextual in meaning. Clean code can be hardcoded into a system, and sometimes a dirty hack can written in a way that’s easy to turn off. Sometimes the code is clean because the filth has been pushed elsewhere. Good code isn’t necessarily clean code.

Code being clean or dirty is more about how much pride, or embarrassment the developer takes in the code, rather than how easy it has been to maintain or change. Instead of clean, we want boring code where change is obvious— I’ve found it easier to get people to contribute to a code base when the low hanging fruit has been left around for others to collect. The best code might be anything you can look at quickly learn things about it.

- Code that doesn’t try to make an ugly problem look good, or a boring problem look interesting.

- Code where the faults are obvious and the behaviour is clear, rather than code with no obvious faults and subtle behaviours.

- Code that documents where it falls short of perfect, rather than aiming to be perfect.

- Code with behaviour so obvious that any developer can imagine countless different ways to go about changing it.

Sometimes, code is just nasty as fuck, and any attempts to clean it up leaves you in a worse state. Writing clean code without understanding the consequences of your actions might as well be a summoning ritual for maintainable code.

It is not to say that clean code is bad, but sometimes the practice of clean coding is more akin to sweeping problems under the rug. Debuggable code isn’t necessarily clean, and code that’s littered with checks or error handling rarely makes for pleasant reading.

Rule 1: The computer is always on fire.

The computer is on fire, and the program crashed the last time it ran.

The first thing a program should do is ensure that it is starting out from a known, good, safe state before trying to get any work done. Sometimes there isn’t a clean copy of the state because the user deleted it, or upgraded their computer. The program crashed the last time it ran and, rather paradoxically, the program is being run for the first time too.

For example, when reading and writing program state to a file, a number of problems can happen:

- The file is missing

- The file is corrupt

- The file is an older version, or a newer one

- The last change to the file is unfinished

- The filesystem was lying to you

These are not new problems and databases have been dealing with them since the dawn of time (1970-01-01). Using something like SQLite will handle many of these problems for you, but If the program crashed the last time it ran, the code might be run with the wrong data, or in the wrong way too.

With scheduled programs, for example, you can guarantee that the following accidents will occur:

- It gets run twice in the same hour because of daylight savings time.

- It gets run twice because an operator forgot it had already been run.

- It will miss an hour, due to the machine running out of disk, or mysterious cloud networking issues.

- It will take longer than an hour to run and may delay subsequent invocations of the program.

- It will be run with the wrong time of day

- It will inevitably be run close to a boundary, like midnight, end of month, end of year and fail due to arithmetic error.

Writing robust software begins with writing software that assumed it crashed the last time it ran, and crashing whenever it doesn’t know the right thing to do. The best thing about throwing an exception over leaving a comment like “This Shouldn’t Happen”, is that when it inevitably does happen, you get a head-start on debugging your code.

You don’t have to be able to recover from these problems either—it’s enough to let the program give up and not make things any worse. Small checks that raise an exception can save weeks of tracing through logs, and a simple lock file can save hours of restoring from backup.

Code that’s easy to debug is code that checks to see if things are correct before doing what was asked of it, code that makes it easy to go back to a known good state and trying again, and code that has layers of defence to force errors to surface as early as possible.

Rule 2: Your program is at war with itself.

Google’s biggest DoS attacks come from ourselves—because we have really big systems—although every now and then someone will show up and try to give us a run for our money, but really we’re more capable of hammering ourselves into the ground than anybody else is.

This is true for all systems.

Astrid Atkinson, Engineering for the Long Game

The software always crashed the last time it ran, and now it is always out of cpu, out of memory, and out of disk too. All of the workers are hammering an empty queue, everyone is retrying a failed request that’s long expired, and all of the servers have paused for garbage collection at the same time. Not only is the system broken, it is constantly trying to break itself.

Even checking if the system is actually running can be quite difficult.

It can be quite easy to implement something that checks if the server is running, but not if it is handling requests. Unless you check the uptime, it is possible that the program is crashing in-between every check. Health checks can trigger bugs too: I have managed to write health checks that crashed the system it was meant to protect. On two separate occasions, three months apart.

In software, writing code to handle errors will inevitably lead to discovering more errors to handle, many of them caused by the error handling itself. Similarly, performance optimisations can often be the cause of bottlenecks in the system—Making an app that’s pleasant to use in one tab can make an app that’s painful to use when you have twenty copies of it running.

Another example is where a worker in a pipeline is running too fast, and exhausting the available memory before the next part has a chance to catch up. If you’d rather a car metaphor: traffic jams. Speeding up is what creates them, and can be seen in the way the congestion moves back through the traffic. Optimisations can create systems that fail under high or heavy load, often in mysterious ways.

In other words: the faster you make it, the harder it will be pushed, and if you don’t allow your system to push back even a little, don’t be surprised if it snaps.

Back-pressure is one form of feedback within a system, and a program that is easy to debug is one where the user is involved in the feedback loop, having insight into all behaviours of a system, the accidental, the intentional, the desired, and the unwanted too. Debuggable code is easy to inspect, where you can watch and understand the changes happening within.

Rule 3: What you don’t disambiguate now, you debug later.

In other words: it should not be hard to look at the variables in your program and work out what is happening. Give or take some terrifying linear algebra subroutines, you should strive to represent your program’s state as obviously as possible. This means things like not changing your mind about what a variable does halfway through a program, if there is one obvious cardinal sin it is using a single variable for two different purposes.

It also means carefully avoiding the semi-predicate problem, never using a single value (count) to represent a pair of values (boolean, count). Avoiding things like returning a positive number for a result, and returning -1 when nothing matches. The reason is that it’s easy to end up in the situation where you want something like "0, but true" (and notably, Perl 5 has this exact feature), or you create code that’s hard to compose with other parts of your system (-1 might be a valid input for the next part of the program, rather than an error).

Along with using a single variable for two purposes, it can be just as bad to use a pair of variables for a single purpose—especially if they are booleans. I don’t mean keeping a pair of numbers to store a range is bad, but using a number of booleans to indicate what state your program is in is often a state machine in disguise.

When state doesn’t flow from top to bottom, give or take the occasional loop, it’s best to give the state a variable of it’s own and clean the logic up. If you have a set of booleans inside an object, replace it with a variable called state and use an enum (or a string if it’s persisted somewhere). The if statements end up looking like if state == name and stop looking like if bad_name && !alternate_option.

Even when you do make the state machine explicit, you can still mess up: sometimes code has two state machines hidden inside. I had great difficulty writing an HTTP proxy until I had made each state machine explicit, tracing connection state and parsing state separately. When you merge two state machines into one, it can be hard to add new states, or know exactly what state something is meant to be in.

This is far more about creating things you won’t have to debug, than making things easy to debug. By working out the list of valid states, it’s far easier to reject the invalid ones outright, rather than accidentally letting one or two through.

Rule 4: Accidental Behaviour is Expected Behaviour.

When you’re less than clear about what a data structure does, users fill in the gaps—any behaviour of your code, intended or accidental, will eventually be relied upon somewhere else. Many mainstream programming languages had hash tables you could iterate through, which sort-of preserved insertion order, most of the time.

Some languages chose to make the hash table behave as many users expected them to, iterating through the keys in the order they were added, but others chose to make the hash table return keys in a different order, each time it was iterated through. In the latter case, some users then complained that the behaviour wasn’t random enough.

Tragically, any source of randomness in your program will eventually be used for statistical simulation purposes, or worse, cryptography, and any source of ordering will be used for sorting instead.

In a database, some identifiers carry a little bit more information than others. When creating a table, a developer can choose between different types of primary key. The correct answer is a UUID, or something that’s indistinguishable from a UUID. The problem with the other choices is that they can expose ordering information as well as identity, i.e. not just if a == b but if a <= b, and by other choices mean auto-incrementing keys.

With an auto-incrementing key, the database assigns a number to each row in the table, adding 1 when a new row is inserted. This creates an ambiguity of sorts: people do not know which part of the data is canonical. In other words: Do you sort by key, or by timestamp? Like with the hash-tables before, people will decide the right answer for themselves. The other problem is that users can easily guess the other keys records nearby, too.

Ultimately any attempt to be smarter than a UUID will backfire: we already tried with postcodes, telephone numbers, and IP Addresses, and we failed miserably each time. UUIDs might not make your code more debuggable, but less accidental behaviour tends to mean less accidents.

Ordering is not the only piece of information people will extract from a key: If you create database keys that are constructed from the other fields, then people will throw away the data and reconstruct it from the key instead. Now you have two problems: when a program’s state is kept in more than one place, it is all too easy for the copies to start disagreeing with each other. It’s even harder to keep them in sync if you aren’t sure which one you need to change, or which one you have changed.

Whatever you permit your users to do, they’ll implement. Writing debuggable code is thinking ahead about the ways in which it can be misused, and how other people might interact with it in general.

Rule 5: Debugging is social, before it is technical.

When a software project is split over multiple components and systems, it can be considerably harder to find bugs. Once you understand how the problem occurs, you might have to co-ordinate changes across several parts in order to fix the behaviour. Fixing bugs in a larger project is less about finding the bugs, and more about convincing the other people that they’re real, or even that a fix is possible.

Bugs stick around in software because no-one is entirely sure who is responsible for things. In other words, it’s harder to debug code when nothing is written down, everything must be asked in Slack, and nothing gets answered until the one person who knows logs-on.

Planning, tools, process, and documentation are the ways we can fix this.

Planning is how we can remove the stress of being on call, structures in place to manage incidents. Plans are how we keep customers informed, switch out people when they’ve been on call too long, and how we track the problems and introduce changes to reduce future risk. Tools are the way in which we deskill work and make it accessible to others. Process is the way in which can we remove control from the individual and give it to the team.

The people will change, the interactions too, but the processes and tools will be carried on as the team mutates over time. It isn’t so much valuing one more than the other but building one to support changes in the other.Process can also be used to remove control from the team too, so it isn’t always good or bad, but there is always some process at work, even when it isn’t written down, and the act of documenting it is the first step to letting other people change it.

Documentation means more than text files: documentation is how you handover responsibilities, how you bring new people up to speed, and how you communicate what’s changed to the people impacted by those changes. Writing documentation requires more empathy than writing code, and more skill too: there aren’t easy compiler flags or type checkers, and it’s easy to write a lot of words without documenting anything.

Without documentation, how can you expect people to make informed decisions, or even consent to the consequences of using the software? Without documentation, tools, or processes you cannot share the burden of maintenance, or even replace the people currently lumbered with the task.

Making things easy to debug applies just as much to the processes around code as the code itself, making it clear whose toes you will have to stand on to fix the code.

Code that’s easy to debug is easy to explain.

A common occurrence when debugging is realising the problem when explaining it to someone else. The other person doesn’t even have to exist but you do have to force yourself to start from scratch, explain the situation, the problem, the steps to reproduce it, and often that framing is enough to give us insight into the answer.

If only. Sometimes when we ask for help, we don’t ask for the right help, and I’m as guilty of this as anyone—it’s such a common affliction that it has a name: “The X-Y Problem”: How do I get the last three letters of a filename? Oh? No, I meant the file extension.

We talk about problems in terms of the solutions we understand, and we talk about the solutions in terms of the consequences we’re aware of. Debugging is learning the hard way about unexpected consequences, and alternative solutions, and involves one of the hardest things a programer can ever do: admit that they got something wrong.

It wasn’t a compiler bug, after all.

丟給語言模型翻譯

可除錯的程式碼是那種不會讓你摸不著頭緒的程式。有些程式碼會比較難除錯,原因可能是隱含的行為、不良的錯誤處理、含糊不清的邏輯、結構過於鬆散或過於緊密,亦或是處於改動中的程式碼。在一個足夠大的專案中,你最終會遇到自己無法理解的程式碼。

在一個夠老舊的專案中,你甚至會發現連自己曾寫過的程式碼都不記得了——如果不是因為提交記錄的存在,你甚至會懷疑這些程式碼是別人寫的。隨著專案規模的增長,記住每段程式碼的功能會越來越困難,尤其當這些程式碼無法正常運作時更是如此。在無法理解的程式碼上進行修改,最終你只能透過除錯的方式去了解它。

撰寫易於除錯的程式碼,從意識到未來你將無法記住這些程式碼開始。

規則0:良好的程式碼應具備明顯的錯誤

有許多方法論的推銷者認為,撰寫可理解的程式碼應該著重於「乾淨的程式碼」。然而,問題在於「乾淨」的定義往往依情境而異。乾淨的程式碼可能是硬編碼進系統中的,某些骯髒的快速修正反而可以輕鬆移除或停用。有時候,程式碼之所以顯得乾淨,只是因為其他複雜的部分被移到別處。

程式碼的乾淨與否,更大程度上反映了開發者對自身工作的自豪或羞愧,而非它的易維護性或可變更性。因此,比起所謂的「乾淨」,我們更需要的是「無趣」的程式碼,這樣的程式碼使變更點顯而易見——我發現,當專案留下許多簡單問題等待他人解決時,更容易吸引其他人�參與。

良好的程式碼應具備以下特徵:

- 不試圖掩蓋醜陋的問題,亦不試圖讓無趣的問題看起來有趣。

- 錯誤顯而易見,行為清晰可辨,而非隱晦不明。

- 清楚記錄自身的不足,而非試圖追求完美。

- 行為足夠直觀,以致於任何開發者都能想出無數種變更方式。

- 即便是極其糟糕的程式碼,有時過於追求清潔反而會帶來更大的問題。

並非乾淨的程式碼不好,而是過度強調「乾淨」有時反而更像是將問題掃進地毯下。可除錯的程式碼不一定乾淨,而充滿檢查與錯誤處理的程式碼,也未必令人愉悅。

規則1:電腦永遠處於「起火」狀態

電腦「著火」,而且程式上次執行時已崩潰。

程式執行的第一件事,應是確保自己從一個已知的、良好的、安全的狀態啟動,而非盲目進行任務。有時,因為使用者刪除了狀態文件或升級了系統,無法獲取乾淨的狀態副本。儘管程式上次執行時崩潰了,但現在卻被視作第一次執行。

例如,在讀寫程式狀態至檔案時,可能會發生以下問題:

- 檔案遺失

- 檔案損毀

- 檔案版本過舊或過新

- 檔案最後的變更未完成

- 檔案系統撒了謊

這些並非新問題,資料庫從古至今(1970-01-01起)便一直在處理這些狀況。使用像 SQLite 這樣的工具,可以解決許多類似問題。然而,如果程式上次執行時崩潰,可能會導致後續以錯誤的資料或方式執行程式。

以排程程式為例,你可以確定以下事故將會發生:

- 由於日光節約時間的變更,在同一小時內被執行兩次。

- 因為操作人員遺忘已執行過,導致再次執行。

- 因為磁碟空間不足或雲端網路異常,錯過一個小時的排程。

- 執行時間超過一小時,延遲��後續排程。

- 在錯誤的時間點執行。

- 接近午夜、月末或年底等邊界時間點執行時,因數學運算錯誤而失敗。

撰寫健壯的軟體,應假設程式上次執行時已崩潰,並在程式無法確定正確行為時選擇崩潰。與其留下「這不應該發生」的註解,直接拋出例外更有助於除錯,因為當問題發生時,你至少有除錯的起點。

你不必能夠處理所有這類問題——僅需讓程式停止並避免進一步惡化即可。小型檢查機制能夠大幅節省排查日誌的時間,而一個簡單的鎖檔機制則能避免耗費數小時進行備份還原。

易於除錯的程式碼應具備以下特性:

- 執行前先檢查條件是否正確。

- 使程式能夠輕鬆回到已知的良好狀態並重新嘗試。

- 透過多層防禦機制盡早讓錯誤浮現。

規則 2:你的程式正在與自身對抗

Google 最嚴重的 DoS 攻擊往往來自自身系統,這是因為我們擁有非常龐大的系統。雖然偶爾會有外部人士嘗試挑戰我們的極限,但真正來說,沒有人比我們更擅長把自己「打趴」。

這對所有系統來說都是一樣的。

——Astrid Atkinson,《Engineering for the Long Game》

軟體總是會在上次執行時崩潰,現在它則總是耗盡 CPU、記憶體與磁碟資源。所有工作程序都在處理空佇列,所有人都在重試早已失效的請求,而所有伺服器同時因垃圾回收機制暫停執行。不僅系統故障,系統本身還在不斷地試圖破壞自己。

甚至要確認系統是否正在執行本身就相當困難。

檢查伺服器是否運作相對容易,但要檢查它是否正在處理請求則困難得多。如果你不檢查執行時間,程式可能會在每次檢查之間不斷崩潰。有時健康檢查甚至可能觸發程式錯誤:我曾經兩次在不同時間點設計出導致系統崩潰的健康�檢查機制。

在軟體中,撰寫處理錯誤的程式碼最終會發現更多需要處理的錯誤,其中許多甚至是錯誤處理本身導致的。同樣地,效能優化往往成為系統瓶頸的來源——一個在單一標籤中使用流暢的應用程式,當同時開啟二十個標籤時可能會變得難以使用。

另一個例子是當管線中的工作程序執行速度過快,導致在下一個部分有機會跟上之前,耗盡了可用記憶體。用車流來比喻:交通阻塞通常是因為過快的車流造成的,阻塞會以回饋形式向後延伸。某些優化會在高載或重載時導致系統以難以預測的方式失效。

換句話說:系統越快,負載越高;若不設法讓系統適度回應,別驚訝它會崩潰。

回壓(Back-pressure)是一種系統內部的回饋機制,而易於除錯的程式碼,是能夠讓使用者參與回饋循環的程式碼,並能讓使用者了解系統的所有行為,包括意外、預期與非預期的行為。易於除錯的程式碼應該是容易檢查的,能讓你觀察並理解其內部變化。

規則 3:現在不消除歧義,以後就得花時間除錯

換句話說:看著程式中的變數,應該能夠輕鬆推斷發生了什麼事。除了一些令人恐懼的線性代數子程序外,你應該努力使程式的狀態表示得儘可能直觀。這意味著不要在程式中途改變變數的用途。若要指出一項明顯的嚴重錯誤,那就是用同一個變數表示兩種不同的目的。

這同樣意味著要謹慎避免「半謂詞問題」(Semi-predicate Problem),即不要用單一值(如計數器)來表示兩個值(布林值與計數器)。避免使用類似返回正數代表結果,返回 -1 代表無匹配結果的方式。原因在於你可能會遇到需要「0,但為真」這類情況(Perl 5 就有這種特性),或是產生難以與系統其他部分組合的程式碼(-1 在下一部分程式中可能是合法輸�入,而非錯誤)。

除了單一變數用於兩個目的外,使用一對變數表示單一目的也同樣糟糕——尤其當這些變數是布林值時。我指的並不是用一對數字來表示範圍不好,而是用多個布林值來表示程式的狀態,通常暗示著隱藏的狀態機。

當狀態不從上到下順序流動時,最好為狀態建立單獨的變數並簡化邏輯。如果你在物件中有一組布林值,可以將其替換為名為 state 的變數,並使用列舉型別(enum)或字串(若需持久化)。這樣,if 語句會變成 if state == name,而非 if bad_name && !alternate_option。

即使你明確表達了狀態機,也可能會出錯:有時候程式碼中隱藏了兩個狀態機。我在撰寫 HTTP Proxy 時就曾遇到極大的困難,直到我分別為連接狀態與解析狀態建立各自的狀態機,才順利解決問題。當你將兩個狀態機合併為一個時,很難新增新狀態或準確判斷當前狀態應該是什麼。

這更多是關於創造不需要除錯的東西,而非使其易於除錯。通過列出有效狀態,可以更輕鬆地直接拒絕無效狀態,而不是不小心讓一兩個無效狀態通過。

規則 4:意外行為即為預期行為

當你對資料結構的功能不夠清晰時,使用者會自行填補空白——無論是預期中的行為或是意外行為,最終都會在其他地方被依賴。許多主流程式語言的雜湊表可以遍歷,這種行為大多數情況下會保留插入順序。

有些語言選擇讓雜湊表按照使用者的預期行為進行——依照添加順序遍歷鍵,而另一些語言則選擇每次遍歷時返回不同順序的鍵。在後者情況下,部分使用者便抱怨這樣的行為不夠隨機。

悲哀的是,程式中的任何隨機性最終會被用於統計模擬,或更糟的是,用於加密,而任何排序的來源則會被用於排序�操作。

在資料庫中,有些識別碼包含的資訊比其他的更多。當創建資料表時,開發者可以選擇不同類型的主鍵。正確的選擇是 UUID 或與 UUID 相似的東西。其他選擇的問題在於,它們除了身份外,還暴露了排序資訊,即不僅能知道 a == b,還能知道 a <= b,而這些其他選擇指的就是自增主鍵。

自增主鍵是資料庫為每一行分配數字,在插入新行時會增加 1。這會產生一種模糊性:人們不知道哪部分資料是「權威的」。換句話說:你是按主鍵排序,還是按時間戳排序?正如之前對於雜湊表的情況,人們會自行決定正確答案。另一個問題是,使用者很容易猜出附近記錄的其他鍵值。

最終,任何試圖比 UUID 更聰明的做法都會適得其反:我們曾經嘗試過郵政編碼、電話號碼和 IP 位址,並且每次都以慘敗告終。UUID 也許不會讓你的程式碼更容易除錯,但較少的意外行為往往意味著較少的錯誤。

排序並不是唯一會從鍵中提取的資訊:如果你創建的是由其他欄位構成的資料庫鍵,使用者將會拋棄原始資料,僅從鍵中重建。現在你有兩個問題:當程式狀態被存儲在多個地方時,副本之間很容易產生不一致。如果你不確定該修改哪一個,或者不確定自己已經修改了哪一個,那麼保持同步會變得更加困難。

無論你允許使用者做什麼,他們都會去實現。撰寫易於除錯的程式碼是對它可能被濫用的方式進行前瞻性思考,並考慮其他人如何與其互動。

規則 5:除錯是社交的,先於技術的

當一個軟體專案分散於多個組件和系統時,發現錯誤會變得更加困難。一旦你理解了問題的發生原因,可能需要在多個部分協調更改才能修正行為。修復大型專案中的錯誤,更多的是關於說服其他人相信這些錯誤是實際存在的,甚至說服他��們修復是可能的。

錯誤在軟體中持續存在,因為沒有人能完全確定誰對哪些部分負責。換句話說,當一切都沒有書面記錄、所有問題都必須在 Slack 上詢問,而且直到唯一知道答案的人登入之前,什麼問題都無法解決,那麼程式碼的除錯就變得更加困難。

計劃、工具、流程和文檔是解決這些問題的途徑。

計劃是如何移除待命的壓力,建立結構來處理事件。計劃是如何保持客戶通知,當人員待命過久時更換人手,並跟蹤問題以進行變更以降低未來風險。工具是將工作簡化並使其對他人可用的方法。流程是如何將控制從個人轉交給團隊的方式。

人員會變動,互動也會變,但隨著時間推移,團隊會繼續沿用這些流程和工具。問題不在於某一方是否比另一方更重要,而是如何構建一種支持彼此變化的方式。流程也可以將控制移出團隊,所以它並非總是好或壞,但總有某種流程在運作,即使它沒有書面記錄,記錄下來的行為是讓其他人改變它的第一步。

文檔不僅僅是文字檔:文檔是如何交接責任,如何讓新成員快速了解情況,如何將變更傳達給受影響的人。撰寫文檔需要比撰寫程式碼更多的同理心,並且需要更多的技能:沒有簡單的編譯器標誌或型別檢查器,寫下大量文字卻無實際內容也很容易。

如果沒有文檔,怎麼能指望使用者做出明智的決策,或同意使用軟體的後果呢?如果沒有文檔、工具或流程,你無法分擔維護負擔,甚至無法替換當前被賦予這項任務的人。

讓程式碼易於除錯同樣適用於圍繞程式碼的流程,讓程式碼變得清晰,知道為了修正程式碼你需要踩到哪些人的腳。

易於除錯的程式碼也容易解釋。

在除錯過程中,常見的情況是當你解釋問題給別人聽時,自己會意識到問題所在。對方甚至不必存在,但你確實需要強迫自己從頭開始解釋情況、問題及重現步驟,這樣的框架往往足以讓我們洞察答案。

如果可以的話。有時候,當我們尋求幫助時,我們並未詢問正確的問題,這也是我常犯的錯誤——這是如此常見的困擾,以至於有個名字:“X-Y 問題”:我該如何獲取檔案名稱的最後三個字母?哦?不,我是指檔案副檔名。

我們會根據自己理解的解決方案來談論問題,並根據已知的後果來談論解決方案。除錯是一種艱難的學習過程,學會面對意外後果和替代方案,並承認自己錯誤,這是工程師最難做到的事之一:承認自己搞錯了。

畢竟,這並不是編譯器的錯。